Reviews

I ble'r aeth y gwrachod i gyd...? / Where did all the witches go....? 2019

"If spells cast forwards there is also a collapsing of temporalities at play, power in multiple directions, perhaps best clarified by Angharad Davues in her closing night commission. I ble'r aeth y gwrachod i gyd...? (Where did all the witches go...?) presents a dialogue between violin recordings made by Davies herself in Lle Self Capel y Graid, Furnace, and the live presence of the LCMF orchestra (cello solo by Anton Lukoszevieze). The two 'voices' here play in and out of discernible separation, collapsing times and spaces, not so much temporal drag as subtle frictions or scuffing; is the recording then a score or a ghost, or is the score always a ghost? Tension across each cell of our skin that doubles back on itself, the most physically thrilling work of the whole week, the listener has a body, the body is a witch."

Arts Monthly no 433 Feb 2020 : London Contemporary Music Festival: Witchy Methodologies - Review by Irene Revell p 40

gwneud a gwneud eto/do and doagain. all that dust, ATD14 2021

Despite all we know about the violin and the once-new ways that people are playing it, Angharad Davies' album gwneud a gwneud eto/do and do again transports us to another land-scape altogether. We are strangers here and that is good.

The album is a single track, a 52-minute improvisation by Davies on the violin with a nail file woven into the three highest strings. She bows on and around the nail file, varying speed and weight but always with a prestissimo pulse, to arrive at a long meditation that evokes chant, noise and alchemy. By holding a consist-ently fast stroke tempo with repetition, Davies invites introspection without preciousness. Each time I listen to the album, I pick up on new relationships between pockets of sound, like I'm watching the weather on fast forward. Listening to the variety of scratches, both inten-tional and incidental-such is the prismatic beauty of improvisation-bowing of openstrings, pitched and unpitched noise and the surprise entrances of low drones that either arise from the nail file or difference tones, I am made aware of the diversity of choices available to the violinist. With heightened sensitivity to the nail file's affordances when the ear and micare close, we learn that 'noise' is vastly inadequate as one name for all its different types. This is a celebration of the violin's inexhaustibility, something both vulnerable and hardy. The idea forgwneud a gwneud eto/do and doagainwas simple: to give the listener 'an ideaof what it sounds like to play the violin'. For Davies, this meant bringing across the physicality of the instrument, allowing the listener to hearall the sounds that only she can hear. Short of bone conduction, the recording transfers the sensation entrancingly. Davies worked closely with the sound engineer Newton Armstrong to createa fairly faithful document. Armstrong's skill is indisputable - each harmonic burst sparkles with clarity, while noisy rumbles don't carry the usual burden of claustrophobia. The duration of the album is also important in conveying asense of 'the performance of keeping something going'. And here I will reveal what I regard as a spoiler of sorts: the album is not an edited multi-track of various improvisations. It consists of just two layered continuous performances. Davies performed once, pushing this one violin preparation to its limit, and then while listening to the first performance in headphones, performed again. In this way, she could fill in her perceived gaps or waning speed, establishing balance. When I listened to the album for the first time, I had not yet read the liner notes, and assumed the music was the result of digital sound-editing diligence, the aural equivalent of a magic-eye poster. But once I found out that there was very little manipulation, with just two full-length recordings, my perception of the album completely changed. More importantly and perhaps controversially, I think this recording should not be listened to without this knowledge.

Understanding the context of the recording forces us to consider a body that is not visible to us. Music tends towards abstraction, but when we are confronted with the knowledge of durational and technical commitment, we cannot help but imagine Davies labouring over the instrument, the tip of her bow a flurry of movement, or the sheer psychological grit it must have taken to maintain speed and intensity for over 52 minutes. The body is a vehicle in astrange way, we are always moving but not necessarily to or with a destination. We are in-between. From no longer to not yet, at once literal and conceptual, the shifts from imagination to embodied engagement and back again are what hold our attention.

In my opinion, the album note is necessary to frame and direct a listener's experience to help them complete the work. What do we do when something that is supposedly external to the artwork is almost essential for the work to be read? At what point can we continue containing the container of the artwork? Is it possible for the container to be part of the whole without an ask? I disregard the label underneath the artwork in museums as often as the next person, but with this album I want to force someone to know afact before this art experience, because we havelong known the artwork is not solitary, inde-pendent, suspended in a vacuum, and there'sadanger here in regardinggwneud a gwneud eto/do and do againas a sound object, tactile and sta-tic. We must remember our bodies, Davies' body, the body of the violin, from where the sound comes and where it goes.

Being operative listeners, then, is part of our responsibility as well. For us it's also about 'the unknown, and being able to adapt to what happens,and find possibilities'. Listen to this album with headphones, or in concert, when it may one day be performed live with two violinists. Maybe play it over itself for yet another doubling. Activate your own listening experience. In grasping our own agency, we may continue what gwneud a gwneud eto/do and do again has so beautifully contemplated, that music is contextual and never objective. I am grateful that Davies pushed herself to the limit to reveal to us her world full of colour, hue and motion, as well as commitment, perseverance and discipline.

Tempo Magazine - volume 76 issue 301 Jul 2022 - Review by Julie Zhu

The Necessary Temperament

London-based saxophonist John Butcher, who turned seventy this year, has been involved in all kinds of improvised collaborations going right back to the days of the Spontaneous Music Ensemble. He’s also known as a composer, a creator of multi-tracked pieces and for his explorations of different environments (his album Resonant Spaces was recorded in a number of unusual locations in Scotland and the Orkney Islands).

Lower Marsh is a collection of duets, Butcher being the common factor in all of them. The first is with Pat Thomas (electronics), the second and third with bassist John Edwards. The fourth is with violinist Angharad Davies and the fifth with percussionist Mark Sanders.

Butcher is a player with a wide expressive range. The secret of this is probably his tendency to understatement which, wisely, always leaves him with space for the music to expand into. He tends, too, to avoid stereotyped expectations – gestures which one might expect to be brash, for example, are at least as likely to be articulated softly, with attention to detail. And it’s always interesting to hear performers adapt to the company they’re in, in this case, anything from Thomas’ abstract electronics (Butcher’s chord-playing blending into Thomas’ ring-modulations) to Davies’ spacious glissandi.

Anyone interested in the music of Lower Marsh ought to check out Unlockings. This features the same line up, only this time playing as a quartet. Although they’re not sold as such, having listened to them both, I tend to think of them as a double album. As one would expect from the duet album, playing as a quartet, these four create a rich, diverse sound-world, as engaging in their more spacious textures (for example, in the second track, Unlockings II) as they are in their more action-packed jams.

The Glass Changes Shape features Butcher again, only this time playing with the guitarist Florian Stoffner and drummer Chris Corsano. There’s a real sense of common purpose at work here. This is Butcher’s approach – creating space though understatement, as described above – reproduced in triplicate. As jazz-writer Brian Morton put it, ‘These three artists don’t need volume ... Their message is inscribed in elegant lower-case and rarely used aural fonts.’ That this quality is a deliberate stylistic choice and not just an end-result is suggested by the title of the first track: all three players demonstrate ‘The Necessary Temperament’. That’s not to say there’s anything sparse or minimal about what’s going on here. On the contrary, it’s full of movement and rich in ideas, with a discrete touch of gentle humour – something one picks up from the track titles (‘Disaster Laugh’, ‘Terminal Buzz’) even before one plays the music. Even at its most frenetic, there’s always room for subtlety.

Burkhard + Angharad LP Meshes of the Evening Reviews

Spontaneous Music Tribune - Aug 2025

Rosie Middleton & Angharad Davies

...On paper, what she plays would look like nothing: just two notes, a fifth apart. But she fills that slight means with a wealth of nuance...

View large image

The Wire issue 458 Apr 2022 - Review by Robert Barry

Angharad Davies going for a walk

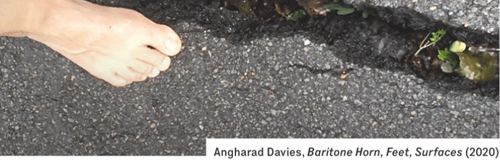

The camera points at two bare feet. They step forward, carefully but decisively, across rocks glistening with moisture. A walk starts to unfold in an unknown location, over lush grass, placid streams, warm pavements. You feel the familiar surfaces and textures, from a close-up perspecitive, last experienced in childhood. Over 14 minutes, the feet pause, turn around, but never stop exploring. They probe every corner of the screen, with the sound of air and musical improvisations in the background.

This short film by Angharad Davies, Baritone Horn, Feet, Surfaces, was broadcast as part of TUSK festival's virtual edition in October. This year, my daily life has bcome distilled into a series of ever decreasing circles (working at the kitchen tables, xercising outside, carefully gettting food). The idea of walking in a straight line and in any direction and for as long as you want felt like e dazzling promise of space exploration, and the little worlds of rock pools and vegetation appeared like miracles of extra-terrestrial life.

The Wire issue 443 Jan 2021 One thing that got me through : Angharad Davies going for a walk - Review by Derek Wamsley p 47

Six Studies Reviews

Confront Recordings - Paul Margree